The Lane Rebels Dismissions

The seminary’s board of trustees eliminated essentially all societies on the campus, and therefore restricted the students’ ability to show their antislavery beliefs and work with the black community in Cincinnati. This elimination of societies upset most of the seminary’s students, so they resolved to take action against it. Approximately 75 students left the seminary. These students decided that their ideals as abolitionists should be the most important thing capturing their attention. Beecher tried his best to encourage the students to stay at Lane Seminary, but they had made up their minds following the decision handed down by the board. The number of students who left was staggering for the school. Beecher wanted to save his ultimate project of spreading the gospel in the western United States, but Lane was never the same again. These Lane rebels became fierce in their ideals of abolition and did what they believed was truthful in response to the decision which took away their right to speak on the radical topic of immediate emancipation. Weld encouraged his fellow students to speak out and tell the rest of the country that they were proud abolitionists. These men spread their ideals across the United States and invigorated many to tell others of their abolitionist beliefs.

A group of former students left Lane Seminary and lived four miles away in a village named Cumminsville. This group of students included William T. Allan, Huntington Lyman, John Tappan Pierce, Henry B. Stanton, and James A. Thome. These students lived, studied, and taught the local black community. The rebels also preached in local black and white churches. A few young men also joined the Cumminsville group who were prospective Lane students, but never attended the seminary. These three men that we know of are: Benjamin Foltz, Theodore J. Keep, and William Smith. They are considered by some scholars to be a part of the Lane rebels, though I do not formally include them in the group. Those individuals, along with the rest of the former Lane students at Cumminsville, attended Oberlin Collegiate Institute. Henry B. Stanton was one of the few at Cumminsville who did not attend Oberlin, instead, Stanton went to law school.

In February 1834, after the Lane Debates occurred, the Tappan brothers’ support for the seminary waned. Arthur Tappan gave the “Cumminsville band” one thousand dollars, showing his support for their work. When the majority of the Lane Students enrolled in the Oberlin Collegiate Institute, the Tappans lent their financial support to that organization on the condition that Charles Grandison Finney was hired as a professor. Finney, the nationally renowned evangelist, agreed.

When the Lane rebels left the seminary, a majority of them decided to go to the recently founded Oberlin Collegiate Institute. Weld did not join them there. Oberlin College was founded in 1834 by Rev. John J. Shipherd a Presbyterian Minister. Two years later, Oberlin was the first college to admit students without regard to race. This historic policy was in part, due to the actions of the Lane Theological Seminary Board of Trustees when one of their outraged members, Reverend Asa Mahan departed to become the first President of Oberlin from 1835 to 1850. He along with Shipherd, led to the policy, “Resolved: That the education of the people of color is a matter of great interest and should be encouraged and sustained at the institution.” This controversial, official policy was approved by one vote, that of Trustee John Keep in 1835. In 1844, the first black student to graduate was George B. Vashon, the first black lawyer admitted to the Bar in New York State. Without the Lane rebels, Oberlin would not have the impetus needed to become a renowned college that accepted all students regardless of race and gender.

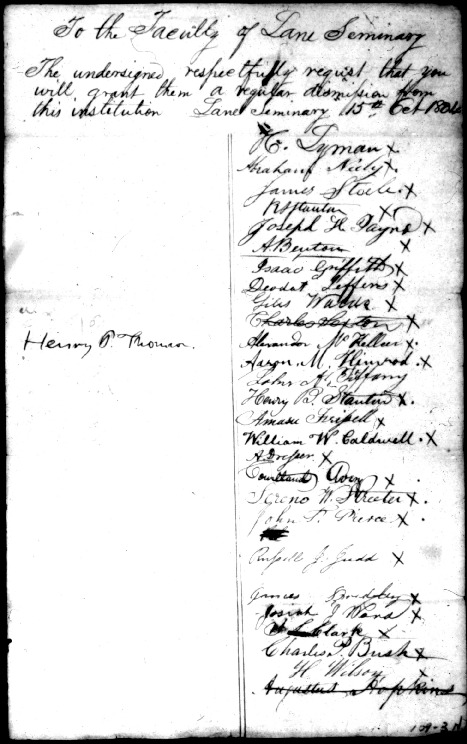

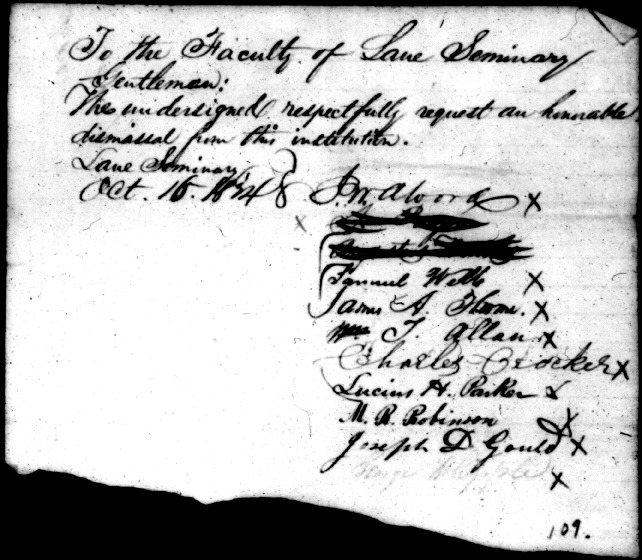

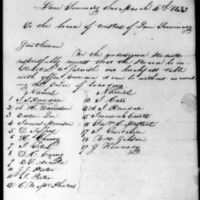

Displayed on the A Cause for Freedom website are two group letters requesting dismission from Lane Seminary, and three individual letters of dismission. The group letters contain signatures of many students who stated their intent to leave the seminary.